Every engineer begins their RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) journey in the “Honeymoon Phase.” It usually starts with a simple Python script: you read a folder of Markdown files, generate embeddings via the OpenAI API, and dump them into a vector database. For the first week, it feels like magic.

The principle is simple: when a user asks a question, the system retrieves document chunks that are semantically similar and feeds them to the LLM as “context.” The LLM uses this context to ground its answers in your actual data. In this phase, search is fast and the LLM is accurate. But this magic relies on a dangerous assumption: that your data is static.

For a project I was building—an AI assistant for a rapidly evolving documentation set—the honeymoon ended the moment the data started to move.

I hit the “Shattered State” problem. As files were renamed, paragraphs shifted, and versions branched, my vector database became a graveyard of orphaned data and conflicting truths. The LLM was now reading “poisoned context”—deleted instructions, outdated API keys, and duplicate chunks that contradicted each other. My assistant was confidently giving wrong answers because its memory was a mess.

I realized that my infrastructure treated ingestion as a stateless pipeline, which is the architectural equivalent of trying to manage a database without a transaction log.

This is the story of why I explored CocoIndex—not as another vector tool, but as a Stateful Context Layer that treats RAG as a cache coherency problem.

The Problem: Five Flaws in Stateless Pipelines

The standard RAG tutorial teaches this pattern:

def rebuild_index():

vector_db.delete_collection("docs")

vector_db.create_collection("docs")

for file in glob("docs/**/*.md"):

chunks = split_into_chunks(read_file(file), chunk_size=512)

embeddings = openai.embed(chunks)

for i, (chunk, embedding) in enumerate(zip(chunks, embeddings)):

vector_db.upsert(

id=f"{file}_{i}", # Position-based ID

vector=embedding,

metadata={"file": file, "chunk_index": i}

)This approach has five architectural flaws.

Flaw 1: Position-Based IDs Create Ghost Vectors

When content shifts, IDs become invalid. If you insert a paragraph at the top of readme.md, every subsequent chunk shifts down by one position. The chunk that was readme.md_0 becomes readme.md_1, but the old vector with ID readme.md_0 still exists in the database—now pointing to content that has moved. Without explicit cleanup, these “ghost vectors” accumulate over time, polluting search results with stale or contradictory information.

Flaw 2: No Change Detection Means O(N) Cost for O(1) Changes

If a single typo is fixed in one file, the pipeline re-embeds all 5,000 files.

The obvious fix—tracking file modification timestamps—fails on three edge cases: deletions leave no file to check, renames look like deletion-plus-creation, and git operations touch timestamps without changing content.

Content hashing improves on timestamps but operates at the wrong granularity. Hash the whole file, and a one-character change triggers re-embedding of all chunks. Hash individual chunks, and you need to track which chunks came from which file—at which point you’re building a state management system.

The root problem: incremental updates require knowing what existed before, what exists now, and which vectors correspond to which source content. Stateless pipelines have none of this information.

Flaw 3: The Consistency Window

While the rebuild runs, your index exists in partial state. Users querying during the rebuild might get zero results (empty index mid-wipe), partial results (half the documents inserted), or stale data (cached queries returning old vectors).

This is the database equivalent of DELETE * FROM users followed by a slow INSERT without a transaction wrapper.

Flaw 4: Migration Breaks Lineage

When you switch embedding models (e.g., text-embedding-ada-002 to text-embedding-3-small), old vectors are incompatible with queries embedded by the new model. When you change chunking strategy from fixed-size to semantic boundaries, every chunk ID changes.

A stateless pipeline treats each migration as a fresh start: wipe the target, reprocess all sources. But production systems often need to run old and new formats in parallel during migration, or roll back if the new approach underperforms. Without lineage tracking, you cannot selectively rebuild one format while preserving another.

Flaw 5: One-Shot Pipelines Require Manual Scheduling

Most RAG scripts run once and stop. Someone must decide when to run the pipeline again. Run too infrequently, and your index drifts out of sync. Run too frequently, and you waste resources on unchanged documents.

The deeper issue: one-shot pipelines treat indexing as an event rather than a continuous process. But keeping an index synchronized with its sources is fundamentally continuous.

The Root Cause

The traditional RAG architecture treats indexing as a pure function: f(source) → vectors. Production requirements demand:

Current State + Delta(source) → New State (atomically)This requires tracking: (1) what content was indexed, (2) what changed, (3) what vectors were produced from each source, and (4) how to apply updates atomically.

The Solution: A Stateful Context Layer

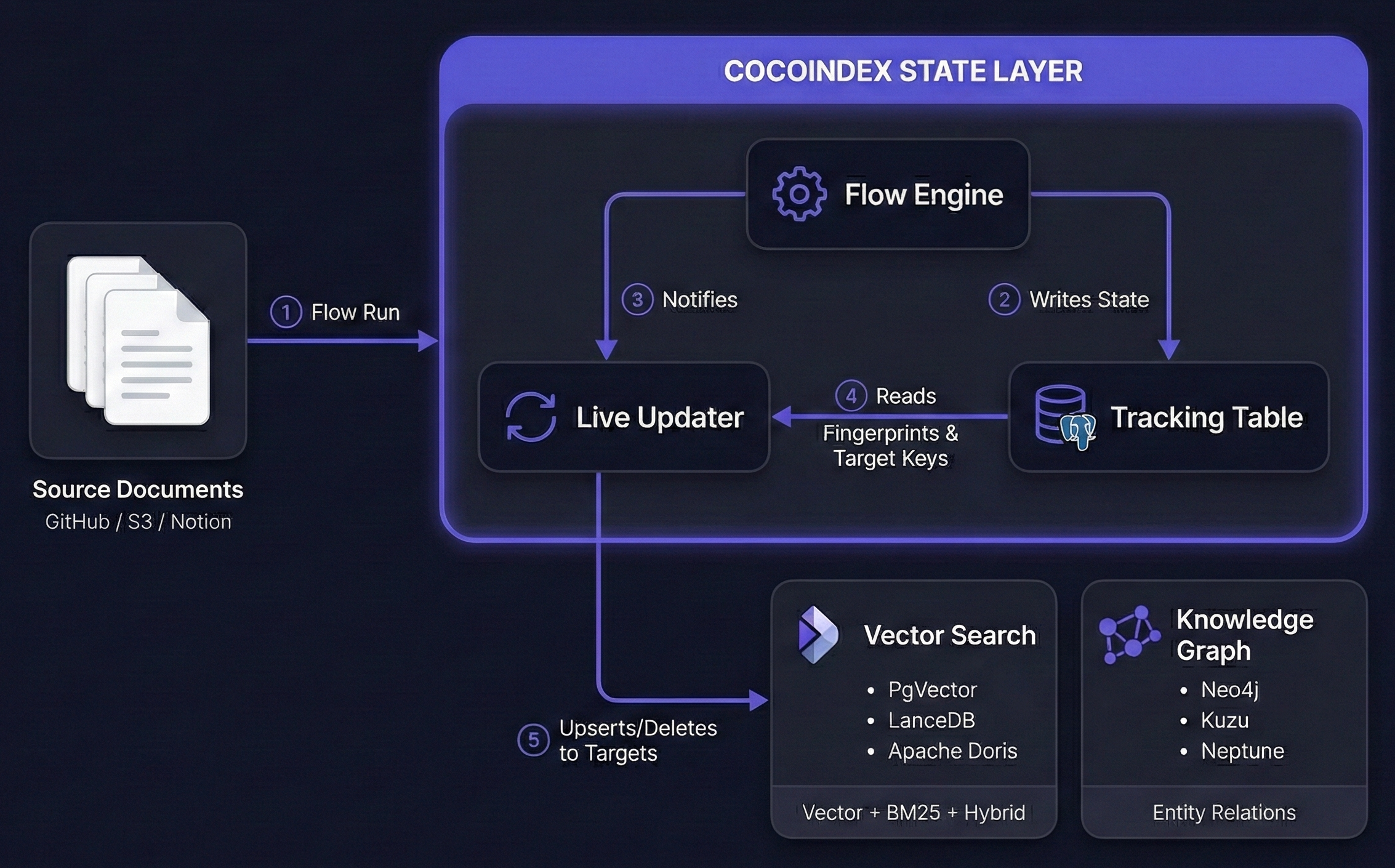

The solution is to treat your vector index like a materialized view—a pattern borrowed from traditional databases. The architecture has three layers:

- Source Layer: Connectors to data sources (GitHub, S3, Notion, etc.), each exposing documents with unique identifiers

- State Layer: A tracking table that stores what has been indexed, how it was processed, and what outputs were produced

- Target Layer: Vector databases, knowledge graphs, or search indices—treated as derived stores that can be rebuilt from the state layer

The system functions like a Kubernetes controller: a reconciliation loop that constantly matches “Desired State” (source files) with “Actual State” (vector index).

Now let’s see how each requirement maps to an implementation.

Requirement 1: Content-Addressable Identity

The principle: Position-based IDs fail because location is unstable. The solution is to identify content by what it is, not where it is.

Implementation: Compute a cryptographic hash (Blake2b, 128-bit) of each document’s content. Two documents with identical content produce identical fingerprints, regardless of filename or location.

import hashlib

def fingerprint(content: bytes) -> bytes:

"""128-bit Blake2b hash for fast equality checks."""

return hashlib.blake2b(content, digest_size=16).digest()

# Move readme.md → tutorial.md?

# Same content = same fingerprint = no re-embedding neededThe choice of Blake2b is deliberate: it provides cryptographic collision resistance without SHA-256’s overhead. The 128-bit output (16 bytes) is compact enough to store efficiently in a database column while providing enough uniqueness that accidental collisions are practically impossible. Comparing millions of fingerprints is fast because it’s just a 16-byte equality check.

This principle applies at chunk level too. Edit one paragraph in a 50-paragraph document, and only that paragraph’s fingerprint changes. The other 49 chunks are recognized as unchanged and skipped entirely.

How CocoIndex implements this: The processed_source_fp column stores a Blake2b hash for each source document. Before processing, CocoIndex compares the current fingerprint against the stored value. Match → skip. Differ → reprocess.

Requirement 2: Two-Level Change Detection

The principle: Content hashes alone cannot detect pipeline changes. If you switch embedding models, every vector is outdated even though source documents are unchanged. You need a second fingerprint for processing logic.

Implementation: Track two fingerprints per document:

| Fingerprint | What It Captures | When It Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Content fingerprint | Source document bytes | Document edited |

| Logic fingerprint | Embedding model, chunking params, output schema | Pipeline config changed |

The decision matrix:

| Content | Logic | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Same | Same | Skip entirely |

| Changed | Same | Reprocess this document only |

| Same | Changed | Reprocess (pipeline rules changed) |

| Changed | Changed | Reprocess |

How CocoIndex implements this: The tracking table stores processed_source_fp (content) and process_logic_fingerprint (pipeline). When you change your embedding model in the flow definition, the logic fingerprint changes automatically, triggering reprocessing of all documents.

Requirement 3: Target Lineage for Atomic Updates

The principle: Vector databases lack cross-document transactions. You cannot atomically delete old vectors and insert new ones. The solution: track which outputs came from which inputs externally, enabling precise delete-then-insert sequences.

Implementation: Store a “receipt” for each source document—the list of target keys (vector IDs) it produced.

Tracking Table:

| source_key | target_keys | content_fp |

|---|---|---|

| readme.md | [chunk_0, chunk_1, …] | 0xAB12… |

| guide.md | [chunk_0] | 0xCD34… |

When readme.md changes:

- Look up old target_keys → [chunk_0, chunk_1, …]

- Generate new vectors → [chunk_0’, chunk_1’, chunk_2’]

- Insert new vectors

- Delete old vectors using stored keys

- Update tracking table with new receipt

The tracking table (in PostgreSQL) provides the transaction boundary. Even if the vector database has no transaction support, the tracking table is the authoritative record of what exists. If step 4 fails, the next run retries using stored keys.

How CocoIndex implements this: The target_keys JSONB column stores the exact IDs of vectors produced from each source. The update sequence—read old keys, generate new vectors, insert, delete, update tracking—happens as a coordinated operation.

CREATE TABLE flow_name__cocoindex_tracking (

source_id INTEGER NOT NULL,

source_key JSONB NOT NULL,

processed_source_fp BYTEA,

process_logic_fingerprint BYTEA,

target_keys JSONB, -- The "receipt"

PRIMARY KEY (source_id, source_key)

);Requirement 4: Continuous Reconciliation

The principle: One-shot pipelines require human scheduling. The solution is a controller loop that watches for changes and applies incremental updates automatically—like a database trigger, but for unstructured data.

Implementation: Two modes of change detection:

- Polling: At configurable intervals, scan sources for modified documents, then run reconciliation on changes only

- Change streams: Subscribe to push notifications (S3 events, PostgreSQL logical replication, Google Drive changes API) for near-real-time updates

Both modes feed the same reconciliation loop:

# Conceptual reconciliation loop

def reconcile(source, tracking_table, vector_db):

for doc in source.changed_documents():

old_state = tracking_table.get(doc.id)

# Fingerprint comparison

if old_state and doc.fingerprint == old_state.content_fp:

continue # Unchanged

# Process and update

new_vectors = process(doc)

vector_db.upsert(new_vectors)

if old_state:

vector_db.delete(old_state.target_keys) # Cleanup via receipt

tracking_table.update(doc.id, doc.fingerprint, new_vectors.keys)How CocoIndex implements this: The FlowLiveUpdater component runs the reconciliation loop continuously. Failures are isolated—if one document fails, others continue. The tracking table records successful processing, so restarts resume without duplicates.

Bonus: Hierarchical Context Propagation

Beyond the five flaws, stateless pipelines also lose document hierarchy. When you slice a document into 512-token chunks, each chunk becomes an isolated string—forgetting which section it came from, which version, what headers preceded it.

CocoIndex’s nested scope syntax preserves hierarchy:

with data_scope["documents"].row() as doc:

doc["pages"] = doc["content"].transform(extract_pdf_elements)

with doc["pages"].row() as page:

page["chunks"] = page["text"].transform(split_recursively)

with page["chunks"].row() as chunk:

chunk["embedding"] = chunk["text"].call(embed_text)

# Propagate parent context to each chunk

output.collect(

filename=doc["filename"], # Grandparent

page=page["page_number"], # Parent

text=chunk["text"],

embedding=chunk["embedding"],

)At query time, each chunk carries its ancestry: “This is from page 12 of security-module.pdf, version 2.3, Authentication section.” The LLM receives hydrated context, not isolated strings.

Summary: Moving from Blobs to Managed Context

Exploring CocoIndex taught me that the “unstructured” in “unstructured data” is a myth. All data has structure; we just lose it when we ingest it poorly.

By moving from a stateless pipeline to a Stateful Context Layer, we gain:

Consistency: The index is a perfect, “anti-ghost” mirror of the source.

Efficiency: We move from O(N) re-indexing to O(Delta) incremental updates.

Intelligence: The LLM receives hydrated context (hierarchy) rather than isolated strings.

If you are an architect building AI infrastructure today, my advice is simple: Don’t just build a pipeline to move data into a vector database. Build a state machine that manages the lifecycle of context. That is what tools like CocoIndex are designed to do.